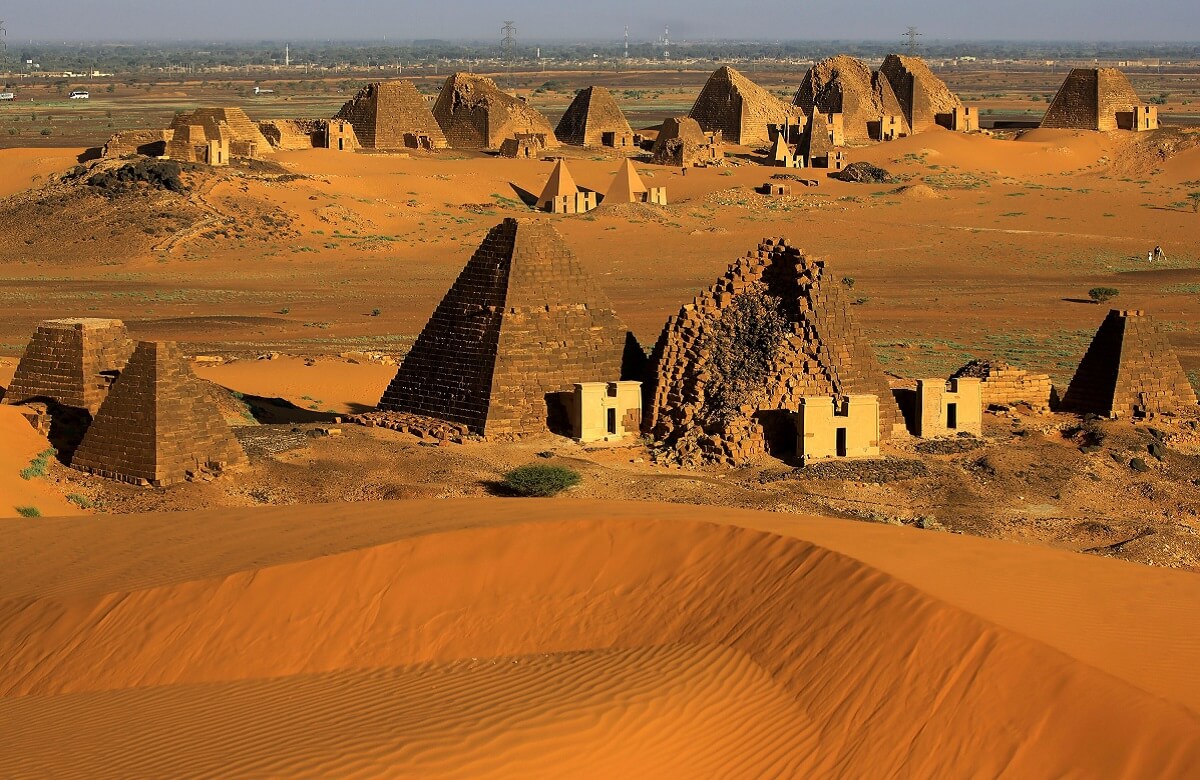

This location, with 250 graves in the largest group of pyramids in the world, unfortunately, for many lovers of cultural monuments, is so inaccessible that only a small number of privileged people had the chance to visit.

While five years ago has been included in the UNESCO list of world heritage, the ancient city of Meroe on the east bank of the Nile is now empty because of the war and economic crisis in northeastern Sudan. However, the ultimate outcome of this adventure is more than worth the effort.

Only the most persistent adventurers can experience and see more than 2000 years old history and the pyramids were used as tombs for kings and queens Meroea. Unlike the pyramids of Giza, these are smaller, but behind them, temples were built. Although a large number of buildings damaged during the great robbery that occurred 200 years ago, many pyramids are preserved in almost perfect condition. Thirteen years ago, in the desert near the Kerme are found dozens of scattered granite statue of the pharaoh. Most were taken to the museum, while a small number still in the desert, waiting for tourists.

Only the most persistent adventurers can experience and see more than 2000 years old history and the pyramids were used as tombs for kings and queens Meroea. Unlike the pyramids of Giza, these are smaller, but behind them, temples were built. Although a large number of buildings damaged during the great robbery that occurred 200 years ago, many pyramids are preserved in almost perfect condition. Thirteen years ago, in the desert near the Kerme are found dozens of scattered granite statue of the pharaoh. Most were taken to the museum, while a small number still in the desert, waiting for tourists.