Beneath the sands of northern Sudan lie the ruins of Meroe, a city as storied as any in antiquity. For almost a millennium – roughly 600 BC to AD 350 – Meroe served as the royal capital of Kush, a powerful African kingdom that at times stretched from Khartoum to the Nile’s fifth cataract. In an era when Rome battled the Parthians and Egypt’s Ptolemies held sway, Kushite queens Kandakes ruled here with equal vigor. One is immortalized by name: Amanirenas, who in 23 BC marched north against Rome, capturing statues of Augustus and notoriously burying the Emperor’s bronze head at Meroe’s temple steps. Such dramatic episodes hint at a civilization once defiant and well-connected – yet one that became obscured in Western history.

Today Meroe is celebrated as “Africa’s forgotten empire”. Its landscape bristles with pyramids, temples and palaces – more than 200 monuments in all – that bear witness to a sophisticated, literate culture. As British-Sudanese scholar Zeinab Badawi observes, “the archaeological remains reveal a fascinating and uncelebrated ancient people the world has forgotten”. This article aims to rediscover Meroe’s legacy: tracing its geography, history, monuments, society and ultimate decline, and assessing how modern conflict has imperiled this UNESCO World Heritage site. (All dates in AD are CE.)

The name Meroe (originally Medewi or Bedewi, meaning “mouth of the reed”) marks one of Africa’s oldest cities. Nestled on the Nile’s east bank in present-day Sudan (roughly 200 km northeast of Khartoum), Meroe occupied an elevated desert plain bordered by tributaries of the Nile. It lay at the edge of the Butana region, between the Nile, Atbara and Blue Nile (hence its UNESCO designation “Island of Meroe”). These lifelines made Meroe fertile and resilient in a semi-desert climate. Its precise coordinates are about 16°56′N, 33°43′E. Today the modern village of Begrawiya (Bagrawiyah) sits among the ruins; the ancient name survives there in a slightly altered form.

Meroe’s story begins in prehistory. Archaeological surveys have found Neolithic pottery in the area dating to the 7th millennium BC. Though no continuous city existed then, these finds mean people camped or farmed here millennia before the pyramids. By the Iron Age (around 900–700 BC), Meroe had emerged as a significant settlement. Its earliest monumental structures – palaces and temples – appear in the 8th–7th centuries BC, part of the broader Kerma/Napatan cultural horizon. The city even appears on New Kingdom Egyptian records and on Greek texts. Herodotus (5th c. BC) describes Meroe (as “Ethiopia’s mother city”) with legendary detail: he mentions its “fountain of youth” and that prisoners were chained in golden fetters because copper was deemed too precious. Though semi-mythical, Herodotus’s account confirms Meroe was well known in antiquity.

Archaeologists divide Meroe’s occupation into three main eras:

By its zenith Meroe was a mature city. The ruins (covering some 10 km²) reveal a walled royal quarter (a rectangular citadel roughly 200×400 m enclosed by thick walls) surrounded by residential mounds and industrial zones. Fieldstone and mudbrick buildings filled the royal enclosure: palaces, council halls, and the Sanctuary of Amun (site M260, the largest temple). Beyond the wall lay broad streets and domestic neighborhoods (the “North” and “South” mounds) packed with mudbrick houses, workshops and iron furnaces. Rows of pyramids – the city’s necropolises – sprawl on the desert east of the settlement. A network of wells, cisterns, and earthwork reservoirs (hafirs) captured rainwater, supporting both irrigation and ceremonies.

Meroe did not become Kush’s center by accident. In the 7th–6th centuries BC, Egypt’s Late Period pharaohs pushed south. In about 591 BC, Pharaoh Psamtik II sacked Napata, Kush’s then-capital. In response, King Aspelta and his successors gradually shifted the power base to Meroe. Strategically it made sense: Meroe lay farther from Egypt on the “fringe of the summer rainfall belt,” meaning more reliable local agriculture, and sat atop rich iron ore deposits and hardwood forests – resources crucial for the kingdom’s renowned metalworking. It was also closer to Red Sea trade routes, facilitating commerce with Arabia and beyond. Over the 5th–4th centuries BC, Meroe’s political importance rose as its royal compounds, temples and palaces were built.

By the 3rd century BC Meroe had fully eclipsed Napata as royal city. Akin to shifting the chessboard, the Kushite monarchy quietly moved burial sites with King Arkamani (Ergamenes I, c. 270 BC). After him, rulers built their pyramids at Meroe instead of Napata’s Nuri Cemetery. (Legend has it this break came with Ergamenes defying Napata’s priests, symbolically slaughtering them, though the story likely echoes a transfer of power away from Napata’s temple complex.) With monarchy and priesthood united in Meroe, Napata retained only a residual cult function for a while, centered on the old Amun temple at Gebel Barkal.

Archaeology reveals this transition. Within Meroe’s royal enclosure a grand Processional Way (a broad east–west avenue) led to the Sanctuary of Amun and other temples. Along this route lay minor shrines and administrative buildings. Surrounding the high-walled Royal City (with gate complexes identified near Kassala gate), excavations uncovered courtyard palaces and stacks of stone blocks carved with royal inscriptions. The mudbrick city wall itself has been traced over 200 meters with gateways, suggesting a solid fortress-like precinct. Just outside this wall was the so-called Royal Baths, a large ritual bathing complex with a deep pool (7.25 m) and colonnaded courtyard – possibly built to harness the Nile’s annual flood for irrigation or ceremony.

A brief comparison of Napata vs Meroe captures this shift:

Feature | Napata (pre-600 BC) | Meroe (post-600 BC) |

Role | Religious capital (Amun Temple) | Administrative and royal capital |

Known Burial Site | Royal pyramids at Nuri | Royal pyramids at Meroe (North, South cemeteries) |

Resources | Limited wooded area | Abundant iron ore, hardwood forests |

Geographic Setting | Near 4th cataract | Between 5th–6th cataract, semi-arid (rainfed) |

Trade Access | Nile trade only | Nile and Red Sea routes |

Napata was never truly abandoned; even in the Roman era Kushite kings made pilgrimages there. But for roughly eight centuries, Meroe was the heart of Kushite power. Historians count three broad Meroitic periods (Early, Mid, Late) by differences in art and burial rites. Late Meroitic kings (like Amanitore, 1st c. AD) continued to erect grand monuments in the royal city.

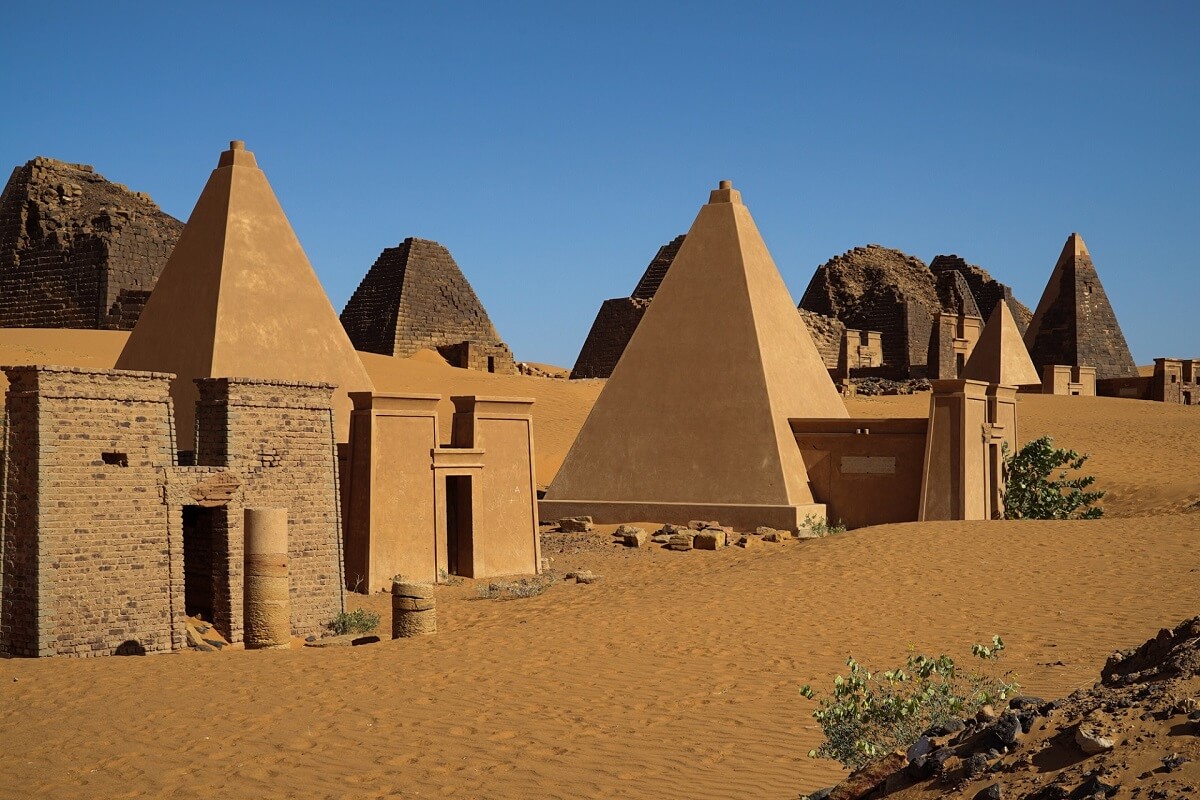

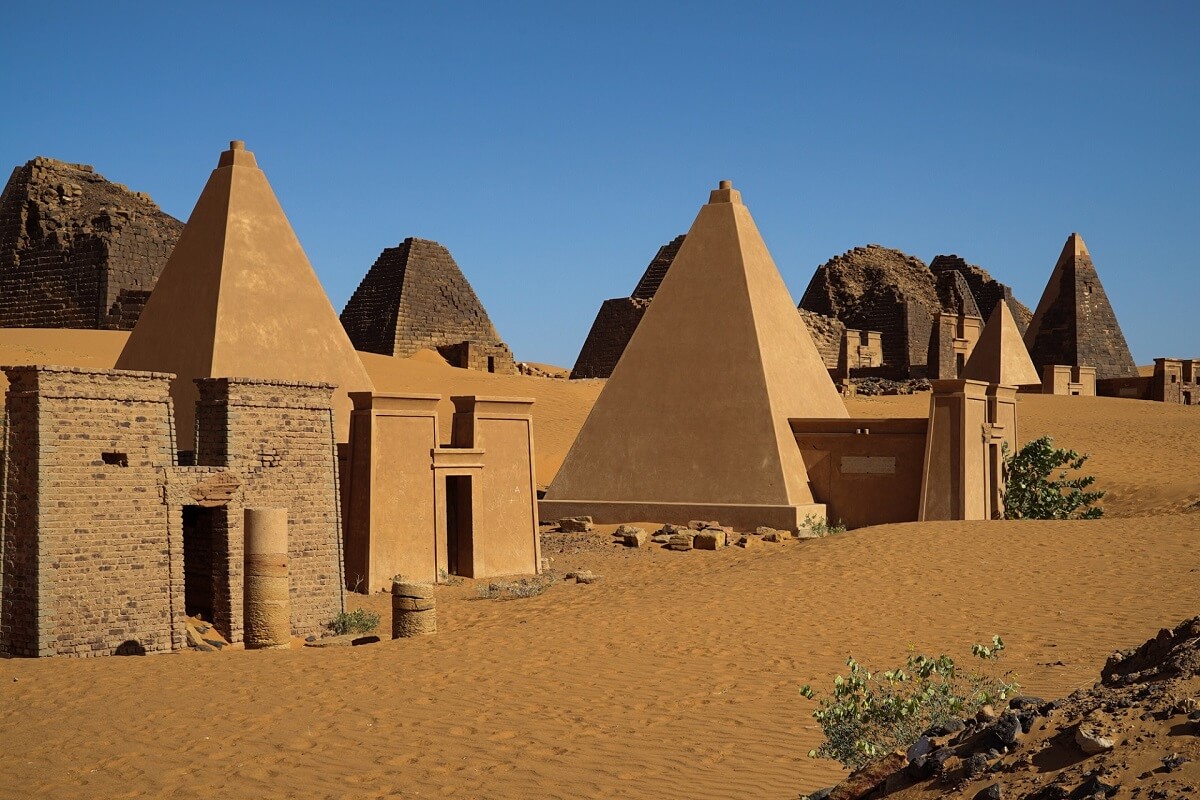

No discussion of Meroe is complete without its pyramids. In the Nile Valley Meroe holds the greatest concentration of such monuments outside Egypt. The royal necropolis east of the city is divided into three cemeteries (North, South, and smaller West). In these lie roughly fifty royal pyramid tombs, each marking a king or queen of Kush. (By contrast, Egypt’s dynastic period built only a few dozen major pyramids in total; Meroe alone rivals that count.) In addition, scores of lesser pyramids (for nobles and high officials) dot the surrounding desert. Overall the site contains more than 200 pyramidal tombs of varying sizes.

These Nubian pyramids look quite different from their Egyptian cousins. Whereas Giza’s Great Pyramid soars at a shallow angle of ~52°, Meroe’s pyramids are much steeper (often 70° or more) and sharply pointed. They were built of local sandstone blocks (and some mudbrick) rather than limestone, with narrow bases and high peaks. Only a few reach above 30 m tall (around 100 ft). To the observer, they appear as slender, elegant spires against the sky. Many have broken tops – not by design but by damage. Early 19th-century explorers looted on-site; the ends of many pyramids were deliberately blown off to reach royal chambers.

| Aspect | Giza Pyramids (Egypt) | Meroe Pyramids (Sudan) |

|---|---|---|

| Built | c. 26th century BC (Old Kingdom Egypt) | c. 300 BC – AD 350 (Kushite period) |

| Height | ~147 m (Great Pyramid of Khufu) | ~20–30 m (up to ~100 ft) |

| Slope Angle | ~51.9° | Steeper (roughly 65–75°) |

| Material | Limestone core with fine casing stones | Sandstone blocks and mudbrick |

| Number (royal) | 3 major pyramids (Khufu, Khafre, Menkaure) | ~50 royal pyramids |

Despite their smaller size, the Kushite pyramids reflect elaborate funerary rites. Each tomb entrance led to multiple underground chambers. Kings and queens were entombed with rich grave goods – gold, jewelry, pottery and even the chariots depicted by the Greek writer Diodorus. Inscriptions and reliefs adorned many burial chambers, showing the deceased before deities like Isis or Apedemak. For example, a 1st-century AD wall-stela in the North Cemetery depicts Queen Shanakdakhete under an arch of ornate columns, a vivid fragment of Kushite art.

The three cemetery sectors themselves formed distinct neighborhoods:

These pyramids attest that Meroe was truly an “African Rome” in global context. Greek and Roman historians noted that Kushite cities matched their own in scale. As the Smithsonian notes, “Each [Meroitic] structure has distinctive architecture that draws on local, Egyptian and Greco-Roman decorative tastes — evidence of Meroe’s global connections.”. In recent years, archaeologists are even reconstructing models of what the city might have looked like: a desert metropolis with temples flanked by sphinxes, palace complexes roofed in painted tile, and hundreds of desert pyramids rising amid gardens of date palms. These reconstructions, though imaginative, remind us that Meroe was once a living city, not just ruins.

Beyond pyramids, Meroe was dotted with sacred temples and public monuments reflecting a unique blend of Egyptian and indigenous culture. Excavations and surveys have identified dozens of structures. The Amun Temple (M260) stands at the heart of the Royal Enclosure. Dedicated to Egypt’s great god Amun-Ra (whom Kushites equated with their own creator deity), this temple was the spiritual center of the capital. Modern research confirms that M260 is the second-largest Kushite temple ever built (only Jebel Barkal’s Amun temple in Napata was larger). Its massive pylon entrance and open courtyard (originally flanked by 4 m-tall gate towers) led into a series of columned halls and a sanctum. Many walls still bear painted scenes of kings and gods. Inscriptions record offerings by King Natakamani and Queen Amanitore (1st c. AD) in the courtyard. The temple was built in two major phases: the first, completed in the 1st century BC, and additional halls and shrines added by various rulers through the 1st–3rd centuries AD. Thus, like the pyramids, Amun Temple grew with the city’s fortunes.

Other deities had shrines too. Apedemak (Lion) Temple (M6) lies just east of the Royal City. Apedemak was a uniquely Nubian god – a lion-headed war deity with Egyptian trappings. The small Lion Temple (site M6) consists of two adjacent chambers within a decorated stone enclosure. Carved reliefs of lion feet still mark the walls, and an inscribed stele names Apedemak’s cult. Found statuary (now in museums) included royal figures flanked by leaping lions. Ancient graffiti depicts the Sun Temple (actually an earlier building) nearby, though that name was a 19th-century misnomer.

A prominent site is Building M250, often called the “Sun Temple” after the classical legend. In reality it was built in the 1st century BC by Prince Akinidad, likely as a local shrine. M250 stands on a large raised terrace approached by high stairs. Atop the terrace is a cella (inner sanctuary) surrounded by a peristyle courtyard. Archaeologists uncovered a wooden sundial shaped like a lion there (a possible solar cult symbol) and Greco-Roman style columns – showing how Kushites blended cultures. M250 was actually built atop remains of an earlier 6th c. BC chapel erected by King Aspelta, highlighting how sacred sites were reused over centuries.

To the north of the city lies Temple M600 (Isis Temple), dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis. It was later repurposed as a medieval Christian church, but its foundations reveal a two-hall sanctuary. At its center stood a faience-tiled altar floor. Finds there include a stele of King Teriteqas (late 3rd c. BC) and large stone statues of the Nubian gods Sebiumeker and Arensnuphis, which once adorned the shrine. (Sebiumeker, often portrayed with a canine head, was associated with fertility and the afterlife; Arensnuphis was a lion god from Upper Nubia.)

One of the most surprising discoveries at Meroe was the so-called “Royal Baths”. In 1912 archaeologist John Garstang uncovered a large bathing complex (M195) within the Royal City. It featured a deep rectangular pool (about 7.25 m deep) with a fountain, surrounded by a colonnaded courtyard. Workers found stone reliefs, faience tiles and the statue of a reclining (obese) royal – initially thought to be a king on a couch. For years Garstang believed it a private bath like those in Rome. Today scholars lean the other way: the complex was likely a ritual water sanctuary, tied to the Nile’s annual flood cycle and agricultural rites. In other words, it may have been a temple for Hapi (Nile god) rather than a literal bathtub. In any case, the ruins – now reburied for protection – include walls painted with bright frescoes and columns in Meroitic style, evidence of high artistry in public architecture.

Several smaller shrines and monuments complete the picture. Along the main processional axis stood pillared entry halls and altars, many marked only by stub walls today. Across the north mound archaeologists have found pottery kilns and iron furnaces – proof of Meroe’s industrial activity (see next section). West of the Royal City lies a rock-cut well and reservoirs (hafirs) that show advanced water management. In short, Meroe was no sparse desert ruin; it was a densely built urban center, with every form of public building from palaces to workshops to formal temples.

Meroe’s art and inscriptions reveal that power was not only male. Kushite succession was matrilineal, and Kandake (often rendered Candace in Greek) – the title for queen-mothers or ruling queens – were famous for military and political leadership. The most legendary of these is Queen Amanirenas. As noted above, around 23 BC Amanirenas led an invasion into Roman Egypt, reportedly sacking Aswan (Syene) and other cities. Strabo, the Greek geographer, described Amanirenas as “a masculine sort of woman, and blind in one eye.”. Despite her injury, she commanded perhaps 30,000 warriors and defeated the Romans in the first round. One of her trophies was a large bronze head of Emperor Augustus, taken (either from Thebes or Philae) and brought back to Meroe. In a final insult, Amanirenas buried that head under the steps of her victory temple at Meroe, so that each worshipper trod on Rome’s emperor. (The head itself was later looted in 1820 by British agents and now resides in London.)

Meroe’s queens ruled openly. Amanirenas was followed by Amanitore and Natakamani (late 1st century BC/AD), a co-regency couple who built many monuments in both Napata and Meroe. Reliefs show Amanitore wielding a sword in procession scenes. Another, Shanakdakheto (c. 170–150 BC), erected the largest pyramid in Meroe (Beg.N.27) and is depicted on it as a warrior. The New Testament legend of the Ethiopian eunuch queen Candace likely refers to one of these Meroitic queens.

These Kandakes underline Kush’s distinctive society. Unlike Egypt or Rome, where women rarely held the throne alone, Kush often had regnant queens. This is evident on its monuments: temple walls routinely show kings and queens sharing honor, and the language of inscriptions treats queens as regnants, not just consorts. When the Roman Empire negotiated peace after their wars, it granted concessions to Amanirenas as Kush’s equal.

Beyond Amanirenas, Meroe’s warriors included the rank-and-file. Excavations have unearthed thousands of iron arrowheads and over fifty horse burials, indicating cavalry units. Inscriptions praise the Kushites as “expert archers,” and artifacts include recurved composite bows of the sort the ancients noted in Ethiopians. So when Rome faced the Kushites, it encountered a fiercely independent civilization whose military prowess was legendary.

Meroe’s wealth was no accident: it was built on resources and trade. A contemporary Greek geographer, Strabo, gawked at the “iron from Ethiopia” he found in Kush, calling it silver by color. He recorded that the Kushite kingdom produced gold, copper, iron, ebony and other exports. Indeed, modern archaeology has confirmed vast iron-smelting sites all around Meroe. On the city outskirts and nearby hills archaeologists have mapped dozens of furnace pits and gigantic slag heaps. At any one time thousands of tons of iron slag (the glassy waste from smelting) lay scattered – earning Meroe the nickname “the Birmingham of Africa.” Meroitic craftsmen made swords, tools and agricultural implements which they traded to Egypt and beyond.

Trade was equally vital. Meroe sat at the nexus of African routes. South of the city lay the fertile savanna of Butana, where farmers grew sorghum, millet, and kept cattle. To the west and south, caravan routes crossed from the Sahel. Meroe’s merchants sent ivory, ostrich feathers, hides and gum arabic north to Egypt. To the east, caravans reached the Red Sea coast (Aksumite Ethiopia’s ports), linking Meroe to Indian Ocean markets. Kushite coins and weights suggest active trade with Arabia and India.

Agriculture supported it all. Though in the semi-desert, Meroe had innovative waterworks. Large underground cisterns and hafir reservoirs collected seasonal floodwaters. The Nile’s inundation – even in this upper Blue Nile bend – was channeled to date palm groves and gardens. Archaeobotanical studies (of pollen and seeds) show fields of millet, barley and beans around the city. Sculptures and reliefs depict river processes and harvest scenes, indicating the centrality of farming. At coronation ceremonies, kings are shown with bundles of sheaves and rams – symbols of abundance and piety.

One product of this innovation was the Meroitic script, used mainly for royal inscriptions and administrative texts. The writing system was derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs but highly abbreviated. Importantly, modern scholars have deciphered Meroitic signs (mapping them to sounds). However, the underlying Meroitic language remains a mystery. Linguists can read the script phonetically, but translating the words has proven elusive. In short, we can hear what the Meroites wrote but not always understand it. This partly accounts for why much of Kush’s own history must be inferred from archaeology and external sources.

Beyond kings and temples, what was it like for ordinary people of Meroe? Archaeology gives surprisingly human details. Estimates suggest the Royal City housed perhaps 9,000–10,000 inhabitants at its peak. They were not all royalty, of course: many were artisans, priests, scribes and administrators. The majority of Kushites lived in villages and farms around Butana – but a substantial community clustered around Meroe’s wall.

Housing and streets: Excavations on the North and South mounds (just outside the citadel) uncovered hundreds of small mudbrick houses. Many were single-room huts; wealthier families had multi-room compounds. House walls were made of sun-dried mudbrick on stone bases. Some interior walls were whitewashed, indicating painted decoration. Relief fragments show homes with thatched or reed-covered roofs. Streets running between the mounds were narrow and likely unpaved. Pottery shards in backyards suggest domestic activities: cooking jars, bowls and storage vessels for grain.

Diet and food: The Meroitic diet was grain-based. Millet and sorghum porridge were staples. Lipid residue studies on pottery and cattle bones indicate heavy consumption of dairy: milk, cheese and butter figured prominently. Raised herds of cattle, sheep, goats and pigs provided meat and fat. Vegetables (legumes, onions) grew in gardens, while date palms (seen in temple reliefs) were prized as royal fruits. Wild game and fish were probably minor supplements, given the semi-arid habitat. Inscriptions also mention honey and beer offerings in temples – implying honey was available from beekeeping and grain fermentation was common.

Work and industry: Many Meroites were craftsmen and workers. In the home workshops people wove coarse linen and leather. But the major industry was metallurgy: blacksmiths smelted iron in slag-filled pits by the city’s edge. From Meroe’s ironworkers came tools that boosted farming, woodcutting (for temple construction), and weaponry for defense. Artisans also shaped gold and copper into jewelry for the elite – for example, gold torcs and bracelets found in queen’s burials.

Society and family: Social status in Kushite Meroe was often hereditary but fluid. Members of royal clans and the priestly class lived in the walled city; artisans and merchants mostly in the satellite mounds. Nubian society valued kinship and tribal ties, but also had defined classes. Inscriptions list titles like “Mayor of Meroe” or “Priest of Apedemak”, indicating bureaucratic roles. Interestingly, the presence of many female skeletal remains with battle injuries suggests women also took up arms – fitting the tradition of warrior queens.

Religion and writing: Religion permeated daily life. Everyone observed local festivals – for example, the “Festival of Unification of the Two Lands” (a Kushite version of the Egyptian New Year) was celebrated at Amun Temple. Deities big and small had niches: household shrines to Isis or Bes have been found in the city. And literate citizens (at least elites) wrote in Meroitic script on ostraca (potsherds) for letters and accounts, though virtually all such texts remain undeciphered. Stone stelae near temples show that literacy was mainly an elite monopoly (priests and scribes) in Meroe.

Historical Note: Ancient visitors marveled at Kushite abundance. Diodorus Siculus wrote that Kush was “a rich and plentiful country” with “good and rich harvests.”

By the late 3rd century AD, Meroe’s fortunes waned. The empire overextended and new enemies arose. In Nubia, nomadic tribes (the Blemmyes) pushed down from the north, gradually eroding Kushite control along the Nile. To the southeast, the Kingdom of Aksum in Ethiopia grew powerful. According to inscriptions and legends, the Aksumite king Ezana (or Ousanas) launched invasions into Kush around AD 330–350. The Napatan monuments at Gebel Barkal and a ruined church at Dangeil show evidence of plunder during these raids. By AD 350 Meroe itself was sacked. Excavators found Greek inscriptions (dated to mid-4th century) boasting “King Ezana conquered Meroe.” The royal city’s temples were stripped of metal and valuables, and at least one later rumor claims vandals twisted and crushed royal mummies.

Despite this assault, Kush did not vanish instantly. Small populations lingered. Burials in Meroe’s desert dunes continue into the 5th century, although on a much smaller scale. Queen Amanipilade, who ruled around AD 300, left one of the last known pyramid burials (Beg. N.25) before the dynasty faded. Scattered communities of Kushites and allied tribes survived in the Butana region, even adopting Christianity in later centuries. But the grand kingdom centered on Meroe was gone. By about AD 420, the Kushite state was effectively extinct.

In the aftermath, Meroe’s buildings stood abandoned. Locals took stones to build new homes in Begrawiya. The Christian Nubian kingdoms to the north (Makuria and Alodia) saw Meroe’s ruins as vaguely sacred or magical, but never reused them for major projects. Over the next 1,500 years, the city was slowly buried by desert winds. Thus Meroe slipped from living memory, leading to centuries of obscurity.

How did such a grand civilization become a historical footnote? Part of the answer lies in 19th-century archaeology. When Europeans first stumbled upon Meroe (a French expedition rediscovered the pyramids in 1821, published in 1826), they assumed the ruins were exotic curiosities. Scholars lacked context: the Meroitic script was unreadable, so no chronicles were readily available. Many early researchers (like Karl Richard Lepsius) focused on Egypt and only later turned attention to Sudan. They sometimes misdated or misinterpreted monuments, viewing Meroe as a mere backwater of Egyptian history. The Napatan (Egyptian-style) temples at Jebel Barkal and the later Roman-era Pyramids at Napata got more attention. Meroe’s wind-bent ruins, 200 km from any major town, simply received less work.

In academia, biases played a role. For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, European and American Egyptologists treated African states as derivative of “classical” models. Publications often referred to Kush as a pale reflection of Egypt. The narrative that Africa had “no history” before European contact contributed to neglect. Even when British archaeologist John Garstang excavated Meroe in 1909–1914, his findings were slow to enter mainstream textbooks. It was not until mid-20th-century scholars like Bruce Trigger and George Reisner pieced together the broader picture that Kushite civilization gained recognition.

A modern factor is location. Sudan’s late discovery of oil and decades of conflict limited tourism and funding. Compared to Egypt’s pyramid fame, Meroe has remained remote. Until very recently, only dedicated researchers and adventurous travelers knew of it. Meroe’s partial script remains undeciphered; without readable history, casual interest lagged.

In sum, Meroe was “forgotten” by Western history due to a mix of colonial-era blind spots, geographic isolation, and the difficulty of reading its own records. Now that archaeological work continues and Sudanese scholars reclaim their heritage, Meroe’s story is re-emerging. As one Sudanese advocate quips, “Kush can be Africa’s cultural anchor, its Athens or Rome – a past of which modern Africans can be proud”.

In 2011 UNESCO inscribed the “Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe” as a World Heritage property, citing its outstanding universal value. This status recognizes the site’s global importance but also underscores a need for protection. Today, Meroe’s monuments face multiple challenges. Sudan’s ongoing conflict (since April 2023) has destabilized the country. While Meroe itself lies far from Khartoum, the war’s chaos has diverted resources. Satellite surveys by UNESCO have begun to monitor the pyramids for looting and damage. Fortunately no major attack on Meroe has been confirmed as of early 2025, but the risk of illegal digs or site neglect is high. In January 2025, Anadolu Agency reported that tourism in Sudan – including to Meroe – had “come to a halt” under the civil war. Locals from nearby Begrawiya lament that guides and camel drivers are idle while hoping the world will “discover the hidden treasures of the pyramids”.

Physically, some pyramids have already suffered. Decades of weathering and earlier excavation attempts (like Giuseppe Ferlini’s 1830s dynamiting) left many monuments in ruin. UNESCO notes that severe sandstorms and groundwater have eroded reliefs. More immediately, landmines and military patrols complicate any fieldwork. Sudan’s own Antiquities Department, underfunded and understaffed even in peace, is stretched thin. International teams who might help are prevented by visa bans and sanctions.

On a positive note, there are efforts to digitally preserve Meroe. Organizations like The Utopian Cloud (a Swiss heritage NGO) have begun 3D scanning the pyramids and temples. Sudanese diaspora groups have launched awareness campaigns. The Sudanese government (pre-conflict) had plans for a Meroe site museum and educational programs, but these remain unrealized.

For those daydreaming of future travel: Meroe is located about 120 km north of Khartoum (by road) and 6 km northeast of the small town of Shendi. The best approach was traditionally via the main highway from Khartoum to Port Sudan (turning off near Wad Ben Naga village). A train station at Kabushiya lies 5 km from the pyramids. On-site, there is no electricity or water for tourists – except solar-powered lamps used by guards. Because of heat, visits were usually scheduled for early morning or late afternoon. The core attractions (the pyramids and royal ruins) are spread over a 2 km sandy expanse east of village. Ruins of the Amun temple and other structures lie west of the highway.

What to bring: When open, a typical visit required strong sun protection, plenty of drinking water (there are no vendors), and a good hat. Guides often asked visitors to keep to marked paths to protect the fragile brickwork. A dash of patience was needed: keepers at the site may light small fires to ward off sandstorms during visits. Photography is encouraged, but climbing on monuments (once common) has been barred to prevent damage.

On-site safety: Even before 2023, hazards included venomous snakes and scorpions in the sand. Tourists are advised to wear boots and stick to day hours. With the ongoing conflict, current dangers include possible stray gunfire or mines. Before the war, tourism police and guards patrolled Meroe at night (rudimentary camp on-site) to prevent lootings. New visitors should check for any “Protected Zone” signage indicating military areas, though the core site itself was not a known frontline.

Amenities: The village of Begrawiya has no hotels; typical tourists camped in tents or returned to Shendi (which has basic hotels). As of 2025 no tourism services (guides, campgrounds) are officially operating due to insecurity. In normal times, travel groups ensured permits from Sudan’s antiquities authority; this may return once conditions allow.

In sum, a future trip to Meroe will require patience and planning. The rewards, however, could be immense: standing amid these pyramids provides a visceral connection to a great African past. As one visitor put it, “entering Meroe is like stepping into an alternate Nile Valley civilization – all at once familiar and completely new.”

Meroe’s monuments stand as mute witnesses to a civilization that was long undervalued in global history. Today, as Sudan and the world wake up to African contributions, Meroe’s rediscovered voice is growing stronger. Its pyramids and temples – once dismissed as mere offshoots of Egypt – are now celebrated as unique expressions of Nubian genius. Researchers emphasize that Kushite civilization, with its own language, script, and innovations (in architecture, metallurgy and governance), deserves a place “at the table” of ancient world heritage.

The story of Meroe reminds us that history is as much about choice as chance. It was geography and human agency that built this city; it was biases and upheavals that nearly erased it. In reconstructing Meroe’s past, we enrich our understanding not just of Sudan, but of the human tapestry. The azure lion-sphinxes and soaring pyramids here narrate a tale of African queens and craftspeople who once looked over all Nile travelers as equals. As we piece together Meroe’s mysteries – often literally, by jigsawing broken stelae and scanning unreadable glyphs – we reclaim a forgotten legacy.

In the words of the archaeologist Claude Rilly, “Just as Europeans look at ancient Greece as their mother, Africans can look at Kush as their great ancestor.” In rediscovering Meroe with fresh eyes and modern scholarship, the world gains a truer picture of history – one where Meroe no longer stands in Egypt’s shadow, but shines in its own right.

Q: What is the ancient city of Meroe?

A: Meroe was the capital city of the Kushite Kingdom of Kush, flourishing ca. 600 BC–AD 350 in what is now Sudan. It became Kush’s royal seat after Napata, serving as a center of religion, administration, and trade. Today its ruins (pyramids, temples, baths) are a UNESCO World Heritage site illustrating Nubian civilization.

Q: Where is Meroe located?

A: Meroe lies on the east bank of the Nile in northern Sudan, about 200 km northeast of Khartoum. It is near present-day Shendi and the village of Begrawiya. The site spreads across both sides of the Khartoum–Port Sudan highway, with its pyramid field to the east and city ruins to the west.

Q: Why is Meroe sometimes called the “forgotten city”?

A: Meroe was long overlooked in popular history. Early archaeologists focused on Egypt, and Meroitic writings were unreadable, so Kushite achievements went underrecognized. It remained outside mainstream study until the late 20th century. The “forgotten” label reflects how this key African civilization was overshadowed by others until recently.

Q: How many pyramids are at Meroe, and how do they differ from Egyptian pyramids?

A: Meroe’s pyramids number in the hundreds overall, with about 50 royal pyramids in the two main cemeteries. They are much steeper and smaller than Egypt’s. Egyptian pyramid sides rise at about 52°, but Meroitic pyramids are sharply pointed (around 70°). Also, Meroe’s pyramids were built of local sandstone and brick.

Q: What was daily life like in ancient Meroe?

A: Meroe had a population of several thousand within the city, plus rural villages around it. Most people were farmers (growing millet, sorghum) and herders (cattle, sheep). Craftsmen made pottery, textiles, and especially iron tools and weapons. Homes were simple mudbrick huts. Important annual festivals and temple rituals were central to their lives. Royal and priestly families lived lavishly in palaces and ate dates, meats and dairy. Slaves and lesser officials also populated the city, as suggested by evidence of large slave pens found near the pyramids.

Q: Who were the Kandakes (Candaces) of Meroe?

A: “Kandake” was the title for queen-mothers or ruling queens of Kush. Meroe’s most famous Kandake was Amanirenas (reigned ~40–10 BC). She led the army against Rome and buried Augustus’s head in a temple at Meroe. Other notable queens include Amanitore, Shanakdakhete and Amanishakheto, who ruled jointly or in succession with kings. The presence of powerful female rulers was a hallmark of Kushite society.

Q: Why did Meroe decline and fall?

A: By the late 3rd century AD, Meroe faced internal and external pressures. Environmental stress (drought) and loss of trade revenues weakened the kingdom. Crucially, the Kingdom of Aksum (in Ethiopia) conquered Meroe around AD 350. The city was plundered and never fully recovered. Afterward, remaining people moved on or integrated into emerging Christian Nubian states.

Q: What is Sudan doing to preserve Meroe today?

A: Meroe is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (inscribed 2011). Sudan’s National Corporation for Antiquities & Museums (NCAM) oversees it. There have been restoration projects on select pyramids and Temples (funded by UNESCO and foreign partners). Digital mapping and site guards aim to protect it. However, as of 2024 Sudan’s conflict has made preservation difficult. International organizations are monitoring the site via satellite and planning inventories of its artifacts.

Q: Can tourists visit Meroe?

A: Under peaceful conditions, yes – Meroe was a popular destination for adventurous travelers. One would typically fly to Khartoum, drive or train to Shendi/Kabushiya, and then hire local guides to reach the site. Visitors could climb pyramids (though this is now discouraged) and walk among the ruins. Facilities were minimal – a campsite in Begrawiya or Shendi hotels. However, as of early 2025, Sudan’s civil war has halted tourism. Visitors should heed travel advisories and await official reopening of the site.

Q: How is the Sudan conflict affecting Meroe?

A: Fighting has been centered elsewhere, but the upheaval affects all heritage sites. Field reports note that local guides at Meroe are idle and concerned for the ruins. Looting of museums in Khartoum worries archaeologists about possible looters moving south. Fortunately, the pyramids themselves are currently standing. UNESCO has expressed deep concern and is conducting damage assessments via satellite. For now, Meroe’s best hope lies in international awareness: every news story about it keeps pressure on warring parties to spare Sudan’s heritage.

Q: Is Meroe a UNESCO World Heritage Site?

A: Yes. The serial nomination “Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe” (which includes Meroe, Naqa and Musawwarat es-Sufra) was inscribed in 2011. Criterion (iv) cited Meroe’s pyramids as “outstanding examples of Kushite funerary monuments”. This status brings some international funding and expertise for conservation.